Dear We Are Teachers,

I’ve taught AP Lit for 12 years and I’m used to the senioritis that sets in this time of year. But this year, it’s like nothing I’ve ever seen. The majority of my students are college-bound and have committed to their school of choice, yet I still have about 35% of my class failing right now. I know they need a wake-up call, but “You will not graduate” doesn’t seem to be working. What’s happening? And how do I help them?

—RUnning on empty

Dear R.O.E.,

Having not taught seniors before, I will defer to our Big Kid expert on staff, Meghan Mathis. Here’s what she had to say:

“That is so rough. Having taught senior English for almost a decade, I know how much effort you’ve already put into helping them get across that graduation stage, and it is SO frustrating when they just seem to refuse to do anything to help themselves get there.

“I’d start by meeting with them one-on-one. Show them their grades and ask them point blank what their plan is when they fail your class, because that’s where their current choices are leading them. Now’s the time to be blunt. ‘How are you going to explain to your family that you won’t be getting your diploma with your class because you’ll need to attend summer school to earn the credits you’re not going to get if you don’t fix things SOON?’ Don’t let them hem and haw. Really ask them to visualize telling their family they failed.

“Once they see where they’re headed if things don’t change, lay out your plan for how the two of you are going to get them to their diploma—together. Yes, they’re seniors. Yep, some of them may even be 18, technically adults. But in reality, many of them still feel like kids who need our help. Have a clear, doable plan in mind for how they can complete the assignments they owe or the tasks they need to finish in order to pass your class. Make sure they’re broken into small, manageable chunks and you have frequent check-in points for them between this meeting and the last day they can turn in assignments.

“Is this a lot? Absolutely. Should you have to be responsible for this? Absolutely not. But if helping these students get their diploma is your goal, you’re going to need to give them a lot of support to get there. End your meeting by letting them know how committed you are to seeing them graduate and how possible it is, IF they follow the plan the two of you have agreed upon. Send them away with one specific task to accomplish and a firm deadline for when you want to see it.

“And if they don’t turn it in? That’s a great time to set up a meeting with your student, their parent(s)/guardian(s), the school counselor, and the principal. Bring the plan so they can see everything you’ve tried so far and determine as a team what the next course of action should be. Good luck!”

(Isn’t Meghan great?)

One thing I would add: Let your principal know that 35% of your AP Lit class isn’t on track to pass and invite them to personally come to encourage your class. Maybe hearing the exact same words from someone else—perhaps the person not handing them a diploma in a few weeks—will jolt them awake.

Dear We Are Teachers,

OK, not sure if it’s just the middle school where I work, but the screaming has become intolerable. Kids are unleashing bloodcurdling screams in class, in the hallways, and at lunch. It’s not just exaggerated reactions to things that are funny, surprising, gross, etc. They are definitely doing it to catch teachers off-guard and see who can get away with it. And so far, they are getting away with it, because my principal thinks this is just normal May rambunctiousness. Can teachers do anything about it?

—i scream for no scream

Dear I.S.F.N.S.,

You have two options: offense and defense. You can play just defense, just offense, or both. (Is that how every sport works? I don’t know. I need to stop with sports metaphors.)

Defense: Get some Loop earplugs. Call home for any of your students who break the rules.

Offense: Tell your principal you’ve received lots of complaints from students about how annoying the screaming in the hallways is and how it hurts their ears. Ask if it’s OK if they practice their email etiquette/advocacy and write you about the issue. Hopefully your principal sees the writing on the wall—that annoyed kids = annoyed parents.

If your principal says, “No thanks, I’ll put an end to this issue now,” great.

If your principal says, “What a great idea! I would love to reply to hundreds of emails this time of year!”, do it! And encourage students to have their parents write similar emails too!

I come back to this idea again and again—that it’s sad that parents can get things moving at school way faster than teachers can. But for now, anyway, it’s the truth. And thus we have to play … defense …? Ugh, I don’t know, OK?!

Dear We Are Teachers,

I’m at the end of my first year teaching 5th grade. My biggest feedback from my administrator this year was to stop taking disrespect and defiance from students personally. I know he’s right (and he gave me this feedback in the nicest way possible), but I don’t know how to “improve” on this. Are there certain strategies or techniques you recommend to compartmentalize a child’s behavior and keep it separate from your human feelings?

—A human (shocking, I know)

Dear A.H.,

Undoubtedly, the single-most helpful thing I learned before I started teaching middle school was the anatomy of kids’ brains. I can’t tell you how many times I thought back to the visual of their shriveled little underdeveloped frontal lobes. To illustrate my point:

A pile of pencil shavings deposited from the pencil sharpener directly NEXT to the trash can instead of inside it? Underdeveloped frontal lobes.

Found “I EAT SH*T TACOS” scrawled into a desk? Underdeveloped frontal lobes.

Stepped on a strategically twisted-up ketchup packet and got ketchup all over my white Air Forces? Underdeveloped frontal lobes.

Seriously, though, it helped a lot to know that my students—even when reactionary or making bad choices—were doing so because they couldn’t biologically do better. This doesn’t mean that they got off the hook or that I dismissed their bad choices. It just meant that I could deal with their behavior without thinking it was a reflection of me or my teaching.

Here are some other pieces of advice—and I’ll link to where I found them so you can read more!

“I learned about behavior, trauma, relationships. And I explore my own trauma history and triggers to build up my coping skills. For example, I focus on being safe for them in a variety of ways: calm voice and body, consistent and clear communication, take accountability for my own actions and mistakes, consistently give a gentle warning before I bring up topics that require a bigger mental and emotional lift, take a breath and be the accepting and unmovable rock when they’re triggered. When I find a behavior especially challenging, I remember kids are good inside and they do well when they can. I remind myself: If they’re not doing well, they’re having a hard time.” —A.W. on our Facebook HELPLINE group

“Two words: rational detachment. You have to stay out of your emotional brain and stick with your thinking brain. Rational detachment is the ability to stay calm and in control—to maintain your professionalism—even in a crisis moment. It means not taking things personally, even with button-pushing comments.” —our article Principals Know How To Keep Cool During Tense Conversations. Here’s How They Do It.

“The best thing about teaching is that we are all human. The worst thing about teaching is that we are all human. So much baggage comes with school. There’s not enough time in the world to figure out why kids say or do what they do. So step back and address what’s happening without personalizing it. The next time you find your patience challenged, ask yourself, What does this student need right now?” —our article 11 Big Classroom Management Mistakes (Plus How To Fix Them)

Finally, if all else fails, imagine them as a baby. Or a dog. Or some other creature that would never twist up a ketchup packet with the intent for it to explode on you.

Do you have a burning question? Email us at askweareteachers@weareteachers.com.

Dear We Are Teachers,

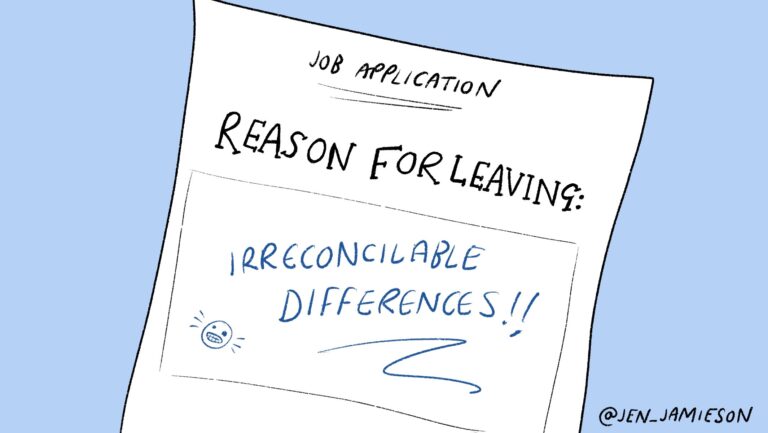

I finally decided to leave a toxic principal and school. I’m applying to a new school in a new district. In the spot where it asks “Reason for Leaving” on the application, I’m wondering what I should put. I’m thinking either “Seeking leadership that reflects my educational philosophy” or “Needed improvement in work culture.” Which would you recommend?

—PEACE OUT!