Are you looking for an authentic way to get your science students to master important concepts, build connections, and engage in high-level academic dialogue? Or maybe you need an engaging activity in the days before a break that still helps meet your standards. Enter hexagonal thinking.

I was first introduced to hexagonal thinking after observing a lesson in a social studies class at my school. The two teachers leading the lesson were following the procedure as described by EduProtocols, and my teaching partner and I were completely inspired by what we saw. A little bit of digging revealed that the concept of hexagonal thinking has been widely discussed in educational media. It’s even been covered here on We Are Teachers. However, while the pieces I read said it could be used for any content, I didn’t see many examples featuring science. Let it be known, hexagonal thinking not only can be used in the science classroom, it’s a great fit for science content! Is your interest is piqued? Read on to learn more about what hexagonal thinking is, and how to bring it to your own science classroom.

What is hexagonal thinking?

Getting started with hexagonal thinking is simple. Each student or team of students receives a set of paper hexagons with key terms printed in the center. The goal is to arrange the hexagons so that each side that touches has a connection. We Are Teachers writer Betsy Potash explains,”Concepts are … moved around to build a web of connected ideas. The most interesting part comes in the debate about where to connect what, and why. No two webs will ever look the same, and neither will the explanations of the connections students have made, whether given in writing or aloud.”

A basic example could be connecting “rain” and “snow” to “precipitation,” since both rain and snow are examples of precipitation. However, students who made this arrangement and allowed one side of “rain” to touch the other side of “snow” would need to be prepared to explain a connection between those terms as well. A surface-level connection could repeat the idea that rain and snow are both precipitation. A more sophisticated explanation could introduce that the two forms of precipitation are both water at varying temperatures. As you can see, the more terms you introduce, the faster the rigor of the activity snowballs (pun intended!).

Beyond vocabulary

I’m sure at this point your brain is buzzing with ways to use hexagonal thinking to reinforce important vocabulary. But don’t limit yourself! Providing hexagons with ideas that reach beyond vocabulary terms is a fantastic way to increase the cognitive demands on your students.

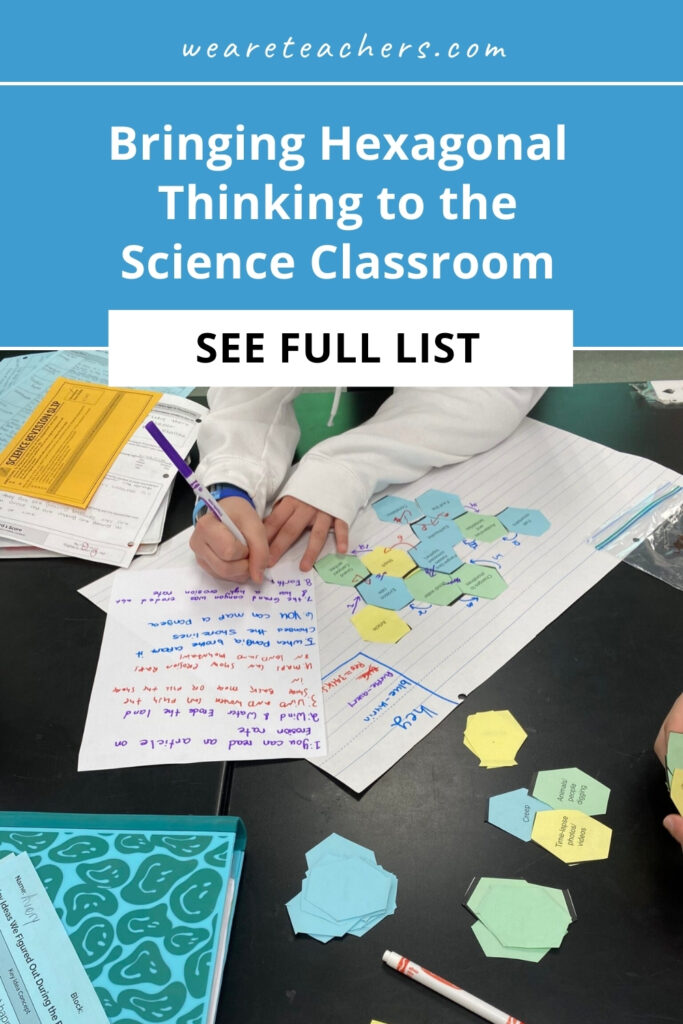

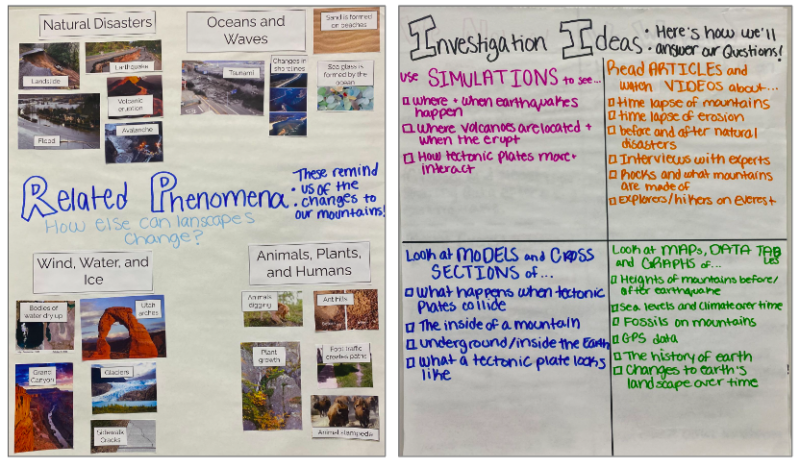

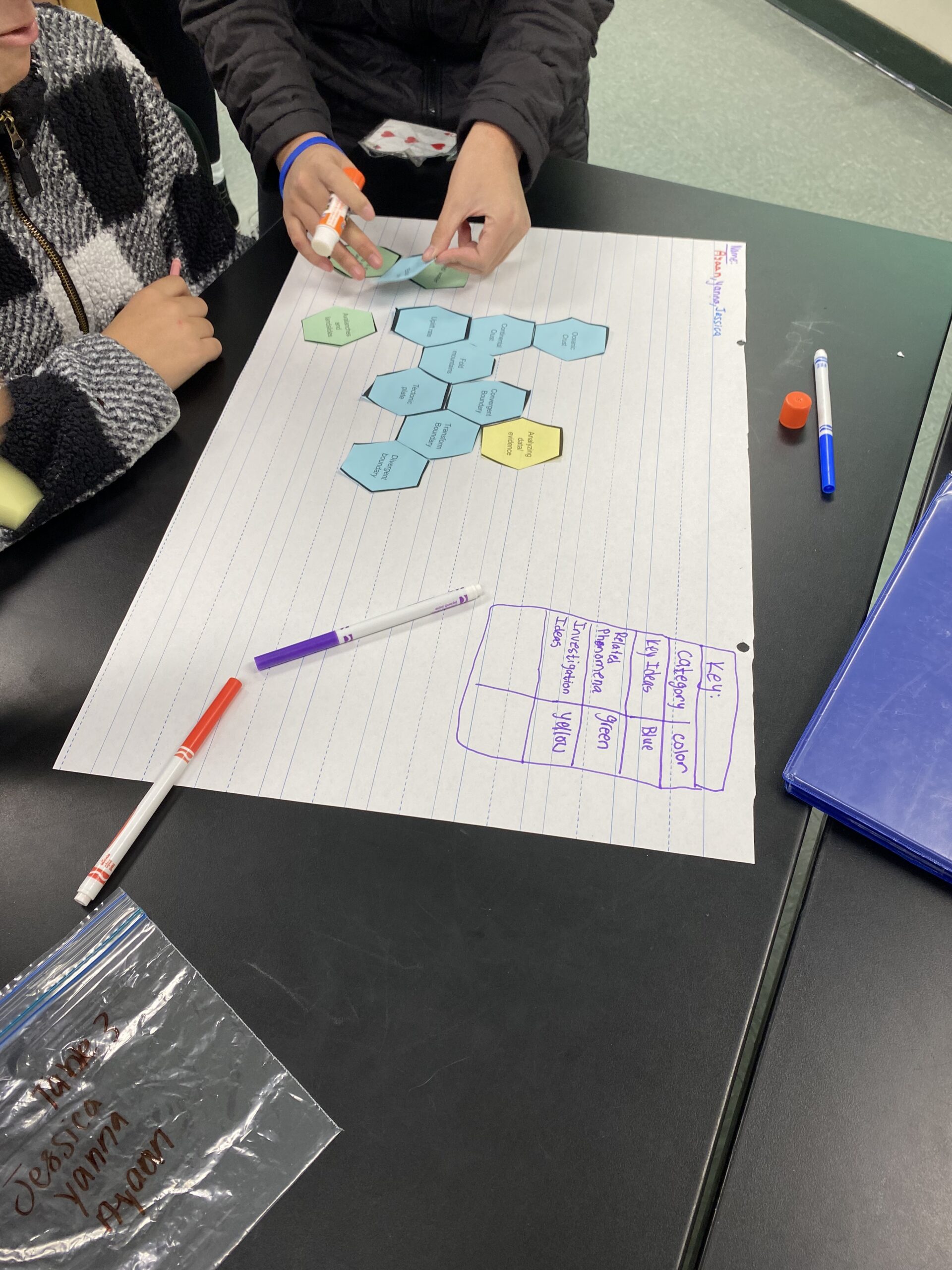

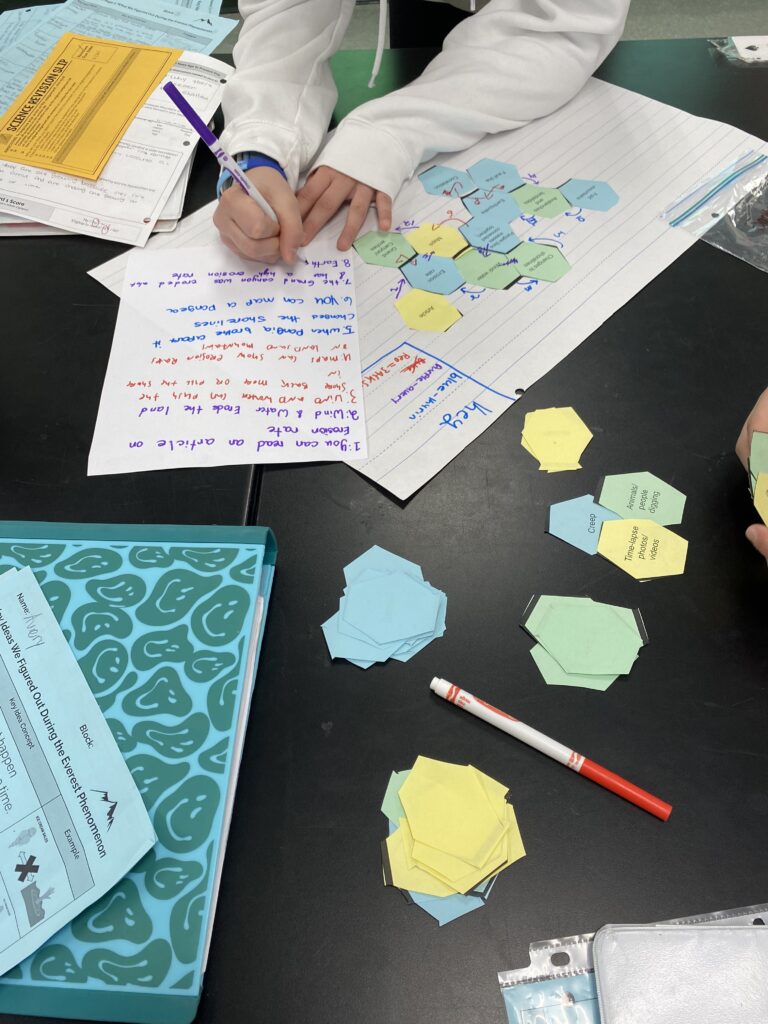

My teaching partner and I chose to implement hexagonal thinking at the end of our unit on plate tectonics. As part of their work with the OpenSciEd model of instruction, students had developed lists of investigation ideas and related phenomena earlier in the unit. We added all of these to color-coded hexagons. The color coding allowed students to visualize connections between the investigations they conducted throughout the unit, scientific concepts they had investigated, and the related science ideas they could now explain using these concepts. Additionally, we provided blank hexagons of each color. This gave students the option to add specific investigations or terms that had not been provided.

Additionally, using different colors allowed us to quickly see how integrated the students’ connections were. Groups that had large clumps of a single color tended to make more literal connections. By contrast, groups with an even mix of colors saw more nuance in how the concepts and activities were connected. Once groups agreed on the arrangement of their hexagons, they glued them to a large sheet of chart paper.

Explaining connections

When it came time for students to explain the connections their team had created, we called on color coding once again. This time, each student in a group of three or four selected a different color marker. Students annotated their team’s chart paper in their chosen color. With a quick look at the chart paper, I could see which group members were actively participating and who needed more support to get started. If one student in the group chose to do their writing in red marker, and their was no red marker on the chart paper, it gave me a cue to check in with this student.

As you can imagine, having four students clustered around a chart paper could get crowded quickly. To keep students from being on top of each other and keep the explanations neat and easier to read, we used a numbering system. Each connection students chose to explain had an arrow with a number connecting the two hexagons. On a separate sheet of paper, students would write the number and the explanation that went with it. Students really took ownership of this and got creative with the placement of their arrows! Some students drew arrows extending through as many as four hexagons, and provided explanations of how the four terms together illustrated a larger concept. I loved seeing their pride and excitement as they realized how many pieces they could put together!

Gallery walk

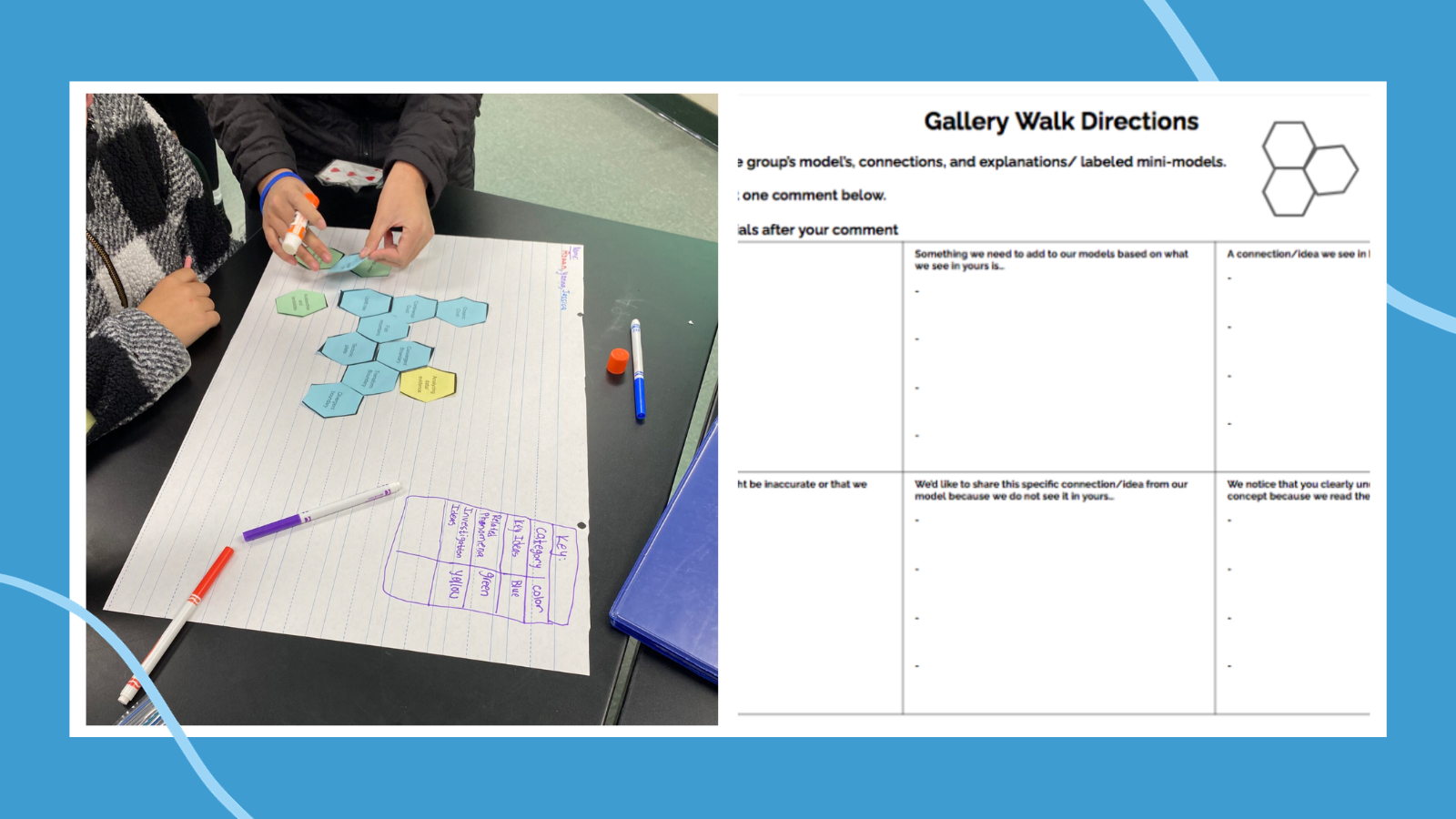

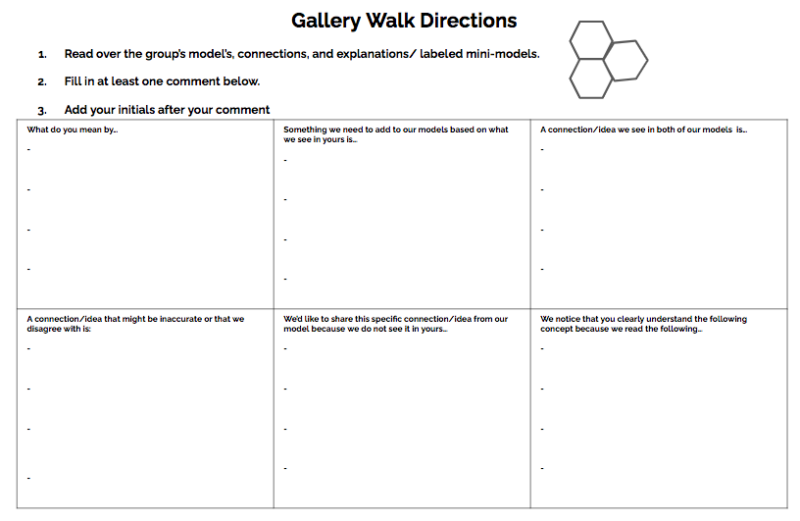

One of the most beautiful things about hexagonal thinking is the diversity of the final products. It was important that we let other groups do a gallery walk to see the connections their classmates had built. However, asking middle schoolers to evaluate one another’s work can be dicey without the proper scaffolds.

To avoid students offering feedback like “your paper is neat!” we provided a sheet of open-ended prompts. Each group left the sheet with their chart paper during the gallery walk. When a group of students arrived at the model, they had two minutes to review the model. Then, the group chose a prompt and responded on the paper. Asking students to provide specific examples of similarities and differences to their own group’s work or questions they had about the paper they were viewing ultimately produced meaningful feedback for their peers.

Student thoughts

Following the activity, my teaching partner and I provided our classes with a survey. We each teach five sections of 7th grade science and got a combined 153 responses. Of those 153, 113 (74%) reflected that the hexagon activity helped them better understand connections between the unit concepts. More impressively, 149 students (97%) shared that the activity “always” or “at times” encouraged them to think deeply. But numbers only tell part of the story.

Reading students’ descriptions of their experiences completing this activity brought the data to life. One wrote, “I think we should do hexagon activities more often. They are really fun and get you thinking about the topic.” Another shared, “It was a great way to show how everything we learned this unit is connected.” It was wonderful to get confirmation from students that they felt the engagement we witnessed in their groups!

More than your typical review

By integrating vocabulary, investigations, and related phenomena, hexagonal thinking was more than just an end-of-unit review. Throughout the activity, my teaching partner and I witnessed true collaboration, teamwork, and high-level thinking from students. If you’re thinking about trying hexagonal thinking in your science classroom, I hope this testimonial is the push you need to make it happen!

For more content like this, be sure to subscribe to our newsletters!