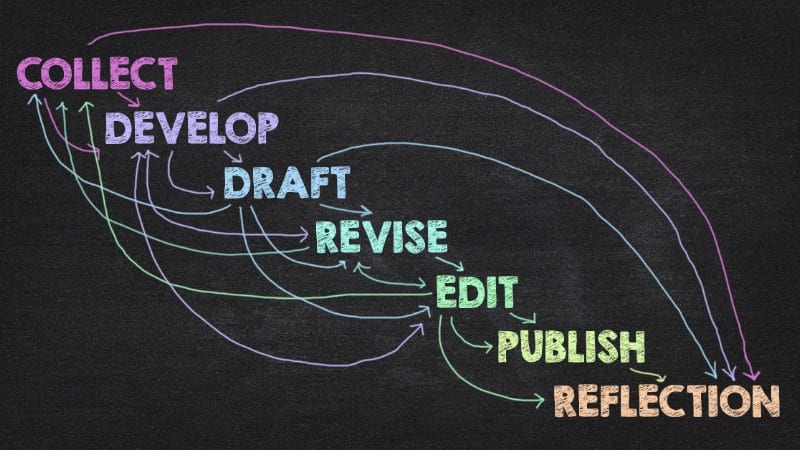

If you conduct an online image search for “writing process,” you’ll find many charts that lay out the steps—brainstorming, drafting, revising, editing, publishing—in a nice linear fashion. It’s as if these visuals assert, “We brainstorm on Monday, draft on Tuesday, etc.”

However, professional writers don’t check off the steps of the writing process as they move through it. As any experienced writer will tell you, the writing process is recursive, not linear.

Sometimes teachers oversimplify the writing process.

And yes, I’m guilty of it too. It is important for students to know the steps of the writing process (i.e., collecting, developing, drafting, revision, editing, publishing, reflection). But it’s also important for them to know that these steps aren’t orderly. For instance, a student might be collecting a seed idea in his or her writer’s notebook, but when they confer with their teacher, they revise. This is part of the process.

Let’s look at one of the hardest lessons for students to learn: editing. Editing shouldn’t be something writers save for the day before publication. Remind your students that writers are constantly editing. Yes, they’re polishing their writing by proofreading it before taking it to publication, but editing is a daily task.

Process logs can help.

One way to help students better understand the “messiness” of writing is to have them reflect on their writing process daily. I like to use “process logs,” a tool that encourages students to log their process and decisions as they go through a specific piece of writing.

Process logs don’t have to be detailed. Students can quickly log what’s easy, what’s hard and/or what strategies/tools they used as a writer on any given day. At the end of a unit of study, students can return to their process logs looking for patterns and stating what they noticed. This helps each student identify a process that works best for him-/herself. This matters because children who understand how they work best as a writer can replicate their writing process again and again across genres.

Before tasking students with keeping a process log, it helps to have tried one yourself. Pay attention to yourself as a writer for a while. Once you understand yourself as a writer, you’ll not only come to understand your process, you’ll be equipped to have meaningful writer-to-writer conversations with your students about the writing process.

The writing process is deeply personal.

As you’re encouraging young writers, it’s important to let them personalize their writing process as much as possible. I believe that as long as a student’s published piece of writing communicates meaning, uses genre knowledge, structures her writing, writes with detail, gives her writing voice, and uses conventions (Anderson, 2005, 17), then it does not matter how she traveled though the writing process to arrive at her final piece.

I often use an image like the one above to remind students just how messy the writing process can be. Sharing a visual like this is freeing since it helps kids understand that while we may occasionally move through the writing process quickly and in a linear fashion, it’s more likely (and perfectly okay) for the steps to become messy or muddled.

Do you use process logs in the classroom? How do you talk about the writing process? Please share in the comments.

WORKS CITED: Anderson, Carl. 2005. Assessing Writers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.