I teach at a school for immigrant kids. That makes some topics really easy to discuss in class—like immigration and racial profiling—but makes the topic of teaching feminism trickier. The reality is, many of my students come from cultures characterized by chauvinism and inequality. Sending my seventh graders home proclaiming to be proud feminists would probably be a bad idea.

However, if some of my students come from a background that deemphasizes the value of women, it’s doubly important that they hear their worth affirmed at school. So here are some ways I do that without crossing the line and having unpleasant conferences with my principal and my students’ parents.

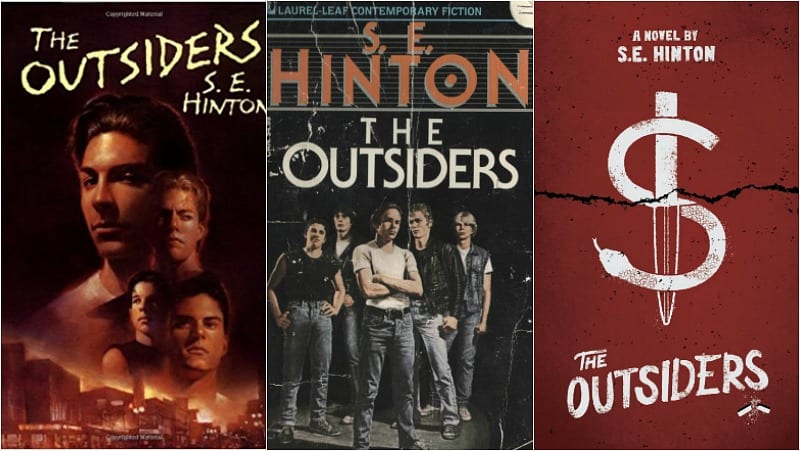

I choose my reading material very deliberately.

I pick books written by women. We talk about the fact that Susan Eleanor Hinton published The Outsiders using her initials rather than her name, because her publisher felt people were less likely to buy a book about gangs written by a woman. We read books with powerful female characters.

When we talk about heroes and read nonfiction articles or discuss current events, we talk about people like Malala, Bree Newsome, or Antoinette Tuff. And while my kids may come from cultures that devalue women, they don’t have to look far to find female role models. Their moms are some of the toughest, most badass women I’ve ever met, and the kids love being able to recognize and brag about the accomplishments of the women who raised them.

I’m always conscious of gender bias in the classroom.

It seems obvious, I know. And I almost wrote “avoid gender bias.” But then I realized, that’s not what I do. Because at least once a week, I hear a teacher or administrator say something like, “I need some strong boys to carry these boxes to the library.” So if I need manual labor taken care of and my girls raise their hands to volunteer, the boys don’t stand a chance. I’ll pick girls every single time. Last week, I got permission to let the kids use a power drill to assemble some new classroom furniture. Every kid got their hands on the drill at least once, but the kids who got a second turn were all my quietest, shyest girls.

I actively call out bigotry from both teachers and students.

A couple of years ago, one of my boys came to me very upset. His math teacher had told him that he was acting like a girl because he was crying at recess. I’ve never criticized or undermined a colleague in front of a kid, but I made it very clear to the student that his teacher was wrong to say that, and then I took it up with the teacher later. By far the most common form of bigotry I see in a middle school classroom, though, is the jokes kids make about gender. “Noah, let one of the girls have a turn at the board next.” “Oh, a girl? Here, George!”

I try to call that stuff out really explicitly, but without embarrassing the student who said it. I usually say something along the lines of, “Noah, I know you were just joking, but that joke bothers me. Because I think the joke is that you’re insulting him by calling him a girl, and since I’m a girl, I’m kind of offended by that. Can you please find a different way to insult George next time?”

I also point out inequality and misconceptions.

Only a handful of my 95 kids have stay-at-home moms. And yet, when we talk about gender roles, tons of them claim that men have to make a living and women should clean the house and take care of the kids. Apparently, 1950s sitcoms inform my kids’ ideas about gender roles more than the actual reality of their lives.

We talk about the fact that the majority of women work outside the home, that moms are more likely to be the sole wage earner for a family than dads. Then we talk about the fact that women are still responsible for the vast majority of household tasks…and that’s unfair. (My girls tend to respond a lot more vehemently and positively to this discussion than the boys, unsurprisingly.) But I believe it’s really important to open up discussion about topics like these.

I try to make small strides in the right direction.

Most of the kids leaving my class at the end of the year are going to think of themselves as feminists. They may not even be familiar with the term. But I’m proud to know they’ll have spent a year discussing and thinking about gender roles, and the way they want to see those roles play out in their own lives.

Hopefully, they’ll leave my class with a renewed understanding of the importance of women to our society in all roles. If nothing else, they’ll look around to see if I’m listening before they try to insult a classmate by calling him a girl. And I guess that’s progress.

What does teaching feminism look like in your classroom? I’d love to hear in the comments.