My school had a lockdown last year—a real one, not a drill. It was scary and awful and I absolutely do not recommend it. The worst part was that while I shepherded four kids (one of whom had the nervous farts) in my classroom on my planning period, my own two children were elsewhere in the school.

When we were all safely together at the end of the day, my kindergartner daughter told me, “My teacher thinks I’m really brave and responsible. She told me if we had to run, I was in charge of holding Jake’s hand and making sure he was safe.”

My daughter was in the co-taught class with students with disabilities. All the teachers had paired up with a student who needed extra help to get out of the building, but there wasn’t another teacher to hold Jake’s hand. So Jake ended up with a protector who didn’t even have front teeth.

The fact that my kid’s class had a workable plan for the students with disabilities—even if it was less than ideal—means we’re doing better than most.

Isabel Mavrides-Calderón—the 18 year-old founder of disability advocacy group Powerfully Isa and one of Teen Vogue’s 21 Under 21, put out a call on her Instagram. She asked people with disabilities whether their K-12 schools had made realistic, practical plans for their safety in an emergency situation, and the answer was a resounding no.

In fact, 80% of students with disabilities reported that their schools could not meet their needs in an emergency situation.

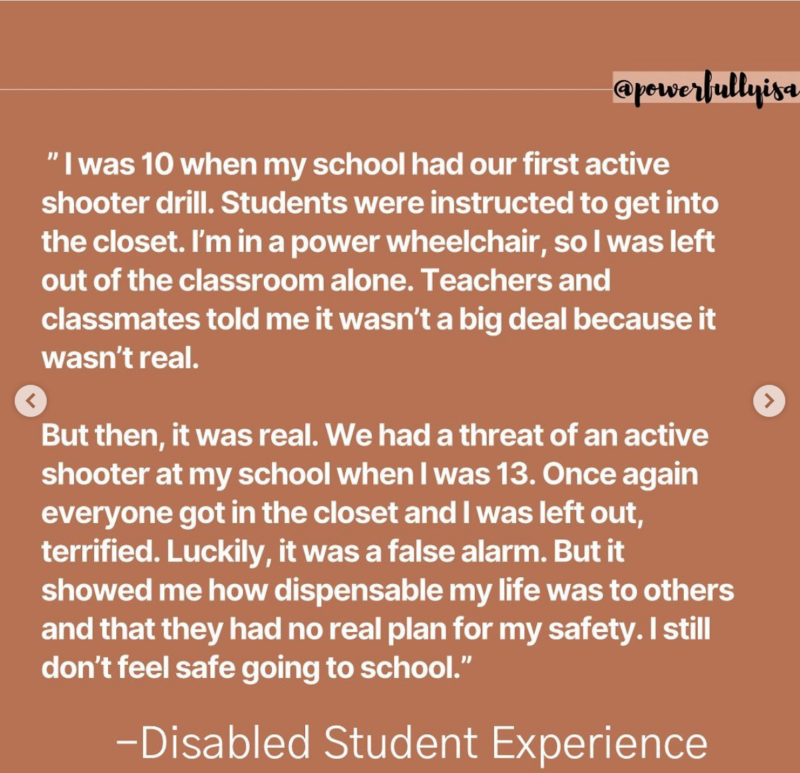

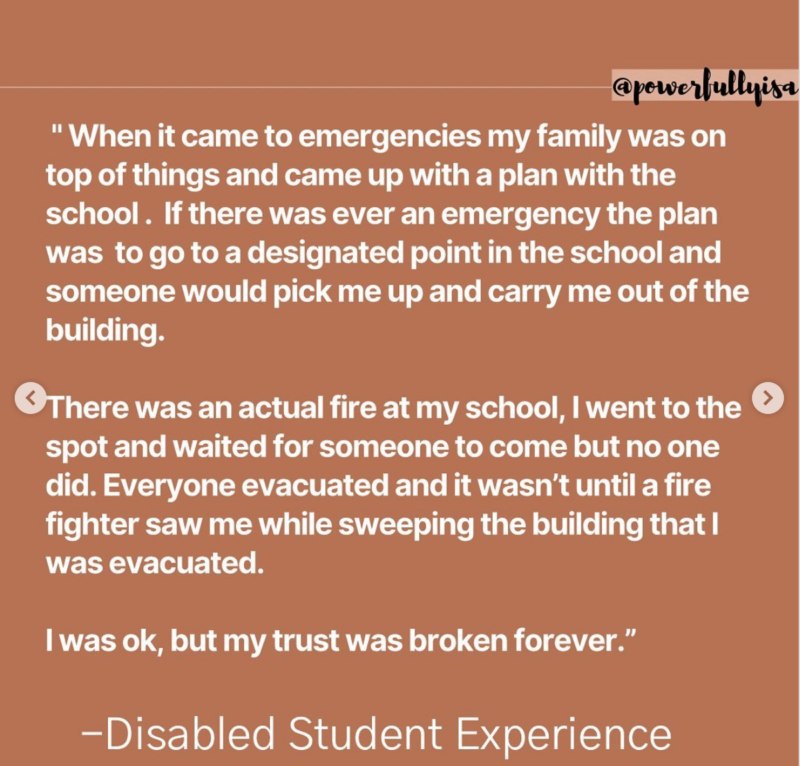

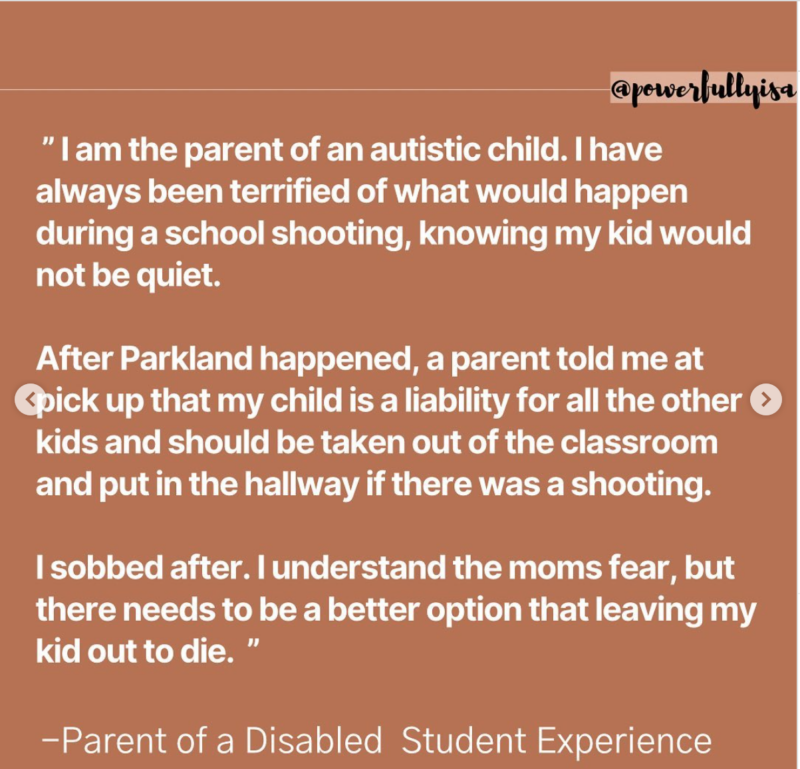

These, Mavrides-Calderón says, are just a few of the stories she heard.

“I was left out of the classroom alone during an active shooter threat.”

“There was an actual fire at my school … I went to the spot and waited for someone to come, but no one did.”

“… there needs to be a better option than leaving my kid out to die.”

So what do we do to fix it?

Full disclosure: I’ve forgotten to take my roster outside with me during every fire drill so far this year. I’m probably not the ideal beacon of emergency preparedness. But, as with every emergency situation, planning and practice seem to be key. My own school’s lockdown system showed some impressive strategizing. They used a buddy system and put teachers with the kids who needed the most help. They paired the kids who struggle less with a responsible, bossy kid like my daughter. It’s not ideal, but Jake would have made it out.

Kids with disabilities should have a second IEP—an Individualized Emergency Plan.

We’ve got to make these early on in the year, and then we have to actually practice them. Several kids who shared their stories on Isa’s post had an important similarity: They had participated in drills where it was obvious that their needs weren’t met. If we see that kids are being left or are unsafe during drills, we’ve got to either practice until we get it right or come up with a new plan, which will also need—you guessed it—practice.

Here are some other ways to be proactive:

- Ask your SpEd coordinator if all students with disabilities have a separate IEP for emergencies.

- Check with your school to see what plans they have in place for students with disabilities.

- Ask what the backup plans are if those staff members who will assist are absent.

- Have your front office brief substitutes on any special emergency plans they should know about.

Teachers are overworked and schools are understaffed, and it feels like every day there’s a new demand regarding our students’ well-being. Just like every other teacher, I’m overwhelmed and afraid a lot of the time. One of the hardest parts of teaching is knowing that we can’t always keep ourselves and our students safe.

But teachers are great at planning. And when we plan ahead, we show our students with disabilities and their families that their lives are as valuable as any other student’s.

Make sure to follow Isabel Mavrides-Calderón on TikTok or Instagram.

For more articles like this, be sure to subscribe to our newsletters.