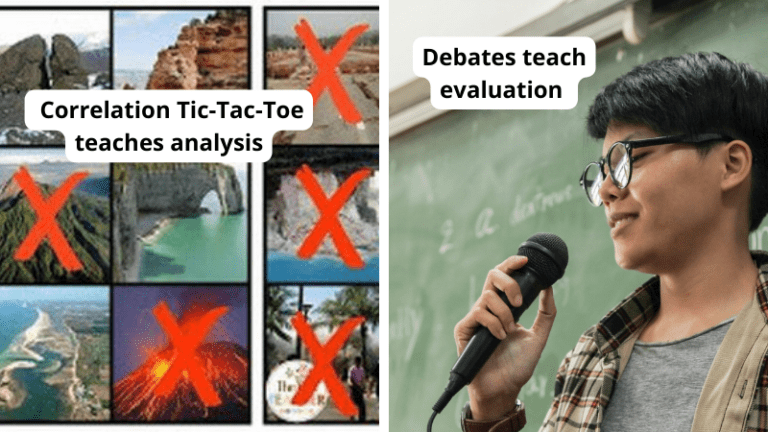

Teaching history with primary sources engages students and develops critical thinking skills. As students practice reading primary sources, they learn that all accounts of the past are subjective. Students construct knowledge as they explore primary texts, forming reasoned conclusions based on evidence and synthesizing information from multiple sources.

Teaching history with primary sources encourages higher-order thinking. As students learn to think like historians, they begin to see cause-and effect-relationships, and how to fit pieces together to understand historical events as part of a whole and complex story in context.

Teaching history with primary sources is an effective way to illustrate abstract concepts and help students make connections between seemingly unrelated ideas and events. Primary texts can provide students with multiple perspectives from which they learn to recognize bias and to question the reliability of sources. By reading a variety of primary texts students discover ways to connect their historical understanding to other subjects, like geography, science, or even math, as well as their modern lives.

America in Class® from the National Humanities Center provides a wealth of primary sources that will work wonderfully with your history curriculum. The National Humanities Center presents these primary texts in classroom-ready lessons, with background information and strategies to help students dig deeper and more acutely understand the past.

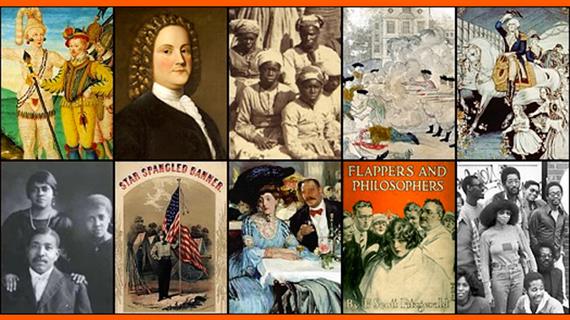

Here are 10 primary source lessons our teacher experts recommend for effective student engagement:

1. Successful European Colonies in the New World

Why did some European colonies thrive while others failed? Through the cooperation and mercy of the Native Americans. This lesson uses two documents, both from the European colonists’ point of view and rife with European biases. These texts work as both a source of 17th-century American history and a provide a lens through which to study the impact of essentializing racial identities.

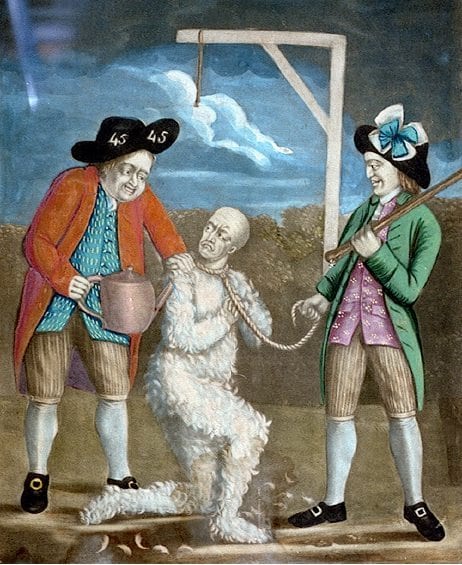

2. Lexington and Concord: Tipping Point of the Revolution

Four primary source documents, both public and personal, paint a vivid picture of the American colonists’ armed conflict with England. These texts also reveal how the American colonists’ values, loyalties, and ideals shifted during the conflict. This lesson takes students beyond the tale of the Boston Tea Party and explores the thoughts and emotions of individuals as they are deciding to separate from a ruling power through war.

3. Abigail Adams and “Remember the Ladies”

Did feminism exist in early American history? The letters of Abigail Adams say yes. While the primary texts of Jefferson, Paine, Henry, and others may be standard sources of the period, Mrs. Adams’s letters provide a fascinating female perspective from the 18th century, as well as an important precursor to the American women’s suffrage movement.

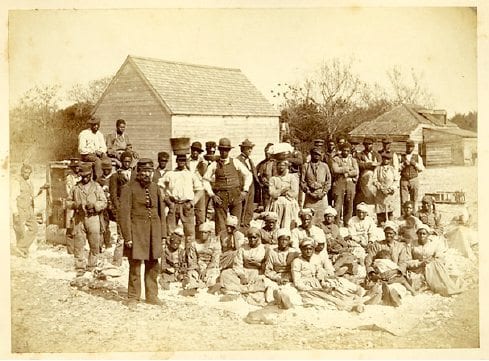

4. The Family Life of the Enslaved

First-person accounts by former slaves, 70 years after emancipation, offer students a view of the ways slave owners fragmented families to control the enslaved. These narratives show the strategies enslaved people adopted in order to preserve their histories and family bonds while under the power of ownership. The testimonies also show the differences in slave experiences, revealing that one individual’s history does not apply to all.

5. The Underground Railroad

Five letters between a white Quaker abolitionist and a free black man in Philadelphia reveal the intricate strategies necessary to move enslaved peoples across state borders to freedom. This lesson pairs perfectly with the primary sources of Frederick Douglass, too.

6. The Enslaved and the Civil War

So much of Civil War history focuses on the military generals and battles fought by white men. This testimony by a freed slave who was a savvy business leader and eloquent speaker illuminates the various ways enslaved men and women fought to obtain their freedom, restored the Union, and abolished slavery. This lesson also includes an exceptional graphic organizer activity that compares and contrasts empirical data and interpretative analyses of that data.

7. The Cult of Domesticity

These passages written by white middle- and upper-class women explore the social norms expected of them and the repercussions on their personal security when they broke with conformity. From articles about obedience to one’s husband to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s and Fanny Fern’s use of fiction to expose the horrors of slavery, these documents can be paired with others like the Declaration of Independence that debate the merits of freedom against the practical considerations of survival.

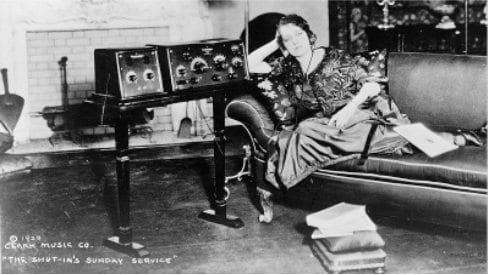

8. The Radio: Blessing or Curse? A 1929 Debate

Your students may be well-versed in the debates regarding use of the Internet and social media at school and at home, and they can explore how the technological innovation of radio in the 1920s brought about similar issues. Students can examine side-by-side editorials that profess that radio is either a boon or a bane to society, and the effects of new technologies on America.

9. The Moral Vision of Atticus Finch

This lesson, a close reading of chapter 11 of To Kill a Mockingbird, takes an in-depth look at some of the more questionable aspects of Atticus Finch’s “moral vision.” It is a fantastic opportunity for English teachers to analyze many of the nearly universally accepted perceptions of Finch, and for history teachers to introduce to students precursors to the civil rights movement.

10. America’s Cold War Blueprint

Why, in 1950, did the United States believe it had to confront the Soviet Union, spreading a cold war across Europe and, later, the globe? This report, requested by President Harry S. Truman of the National Security Council, guided American foreign policy for nearly 40 years. It will help students, many of whom may be learning of the Cold War for the very first time, to understand how it was grounded in American ideas of democracy.

And these are only 10 of the lessons presented! Find even more primary source history lessons at America in Class from the National Humanities Center.