We’re so excited this week to share a guest blog from Dr. Kelli Sandman-Hurley of the Dyslexia Training Institute on what teachers need to know about dyslexia.

As teachers, we get so excited seeing students understand a new concept and grow exponentially in one year’s time. But there is always that group of students in every teacher’s career that they just weren’t able to help the way they wanted to. They knew

the kids were bright. They knew they were motivated to learn. They knew they were supported at home. They knew they had all the opportunities to learn. However, for some reason, these kids just struggled with reading and spelling—despite the

help of teachers and parents. Dyslexia is much more common than most people—even teachers—think. Below are eight things every teacher in every classroom on every school campus should know.

-

Dyslexia is real. Think about this. Autism affects one in 68 children and we hear about autism all the time. What you might not realize is that dyslexia affects one in five people—that’s up to 20 percent of the population. Dyslexia

is a neurobiological difference in the brain that makes reading and writing more difficult to learn (you can find the official definition here.)Remember that reading and writing are man-made

constructs, and not every brain has the ability to learn those constructs without explicit instruction. What this means for teachers is that every single year in every single class sits a student with dyslexia. Dyslexia can look different in each

student. Some may read a little slowly. Some may have extreme difficulty with decoding. Some may be poor spellers. Some may read accurately yet slowly, and then they cannot tell you what they just read. These are all symptoms of dyslexia. Dyslexia

also occurs on a continuum. So it may be mild in one student and severe in another. But this is the annotated version about dyslexia. For more information about dyslexia, you can watch this TED-Ed video or you can visit the International Dyslexia Association. -

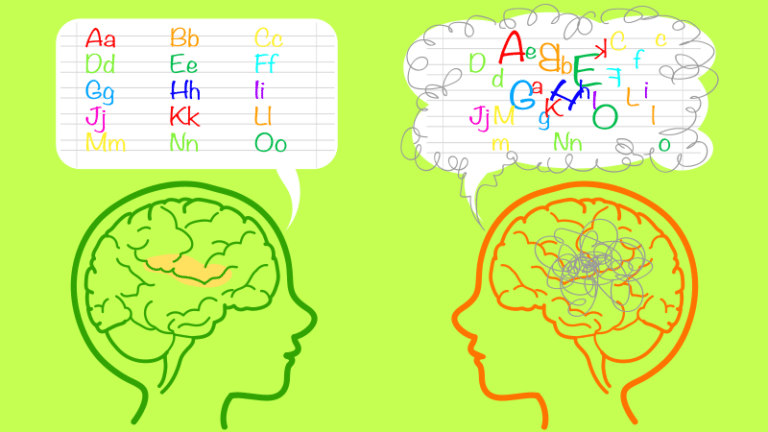

Dyslexia is not a visual problem. People with dyslexia see words and letters the same way people without dyslexia do. Therefore any “intervention” that targets the visual system is misguided. This includes colored paper, covered overlays,

colored lenses and vision therapy. Yes, students with dyslexia do confuse b and d and may say was for saw, but it is not because they “see” the letter or word backwards. It is because they failed to unlearn

that the letters change depending on their place in space. For example, the brain understands that a cow is a cow no matter which way it is looking. So when a child learns to read, they have to learn that the spatial orientation of a letter or

word will completely change the name of the letter. For a more thorough explanation, you can read this example.

The American Academy of Ophthalmologists released this statement about the misuse of vision interventions for students with dyslexia.

The takeaway here is that it is not productive for the student with dyslexia when we try to correct what they see instead of how they process the information. -

Dyslexia is not outgrown. The fact of the matter is that a person is born with dyslexia, and once they are born with dyslexia, they will grow old with dyslexia. But with the correct intervention, they may learn to improve their reading

and writing and hopefully be encouraged to embrace their dyslexia. Ben Foss, a dyslexic and author of The Dyslexia Empowerment Plan, explains, “Whether

your child is on the cusp of being identified or you’ve known about his dyslexia for quite some time, I say welcome to the club! It’s safe here, and you can let go of your fear and anxiety about this identification. Believe me, I know how you

feel. I was there and so were my parents, and I can tell you with 100 percent certainty that it will get better. Indeed, you’re going to have fun.”

The important thing to realize here is that it is unproductive and a bit destructive to tell parents and children to “wait and see” what will happen. Dyslexia can be identified as early as three years old, and the earlier, the better. The “wait-and-see” approach will never work for a child with dyslexia. -

Dyslexia is not an intellectual deficit. When a child with dyslexia is struggling to read, spell, understand or remember what they read, it is not an intellectual deficit. In fact, in order to be diagnosed with dyslexia, a child has

to have a low average or above IQ. It is common for children who are struggling to be inadvertently marginalized by the educational system because educators do not know how to teach them. The takeaway here is that a child with dyslexia has as

much potential as every other student in the classroom. -

A child with dyslexia needs an explicit, multisensory and systematic intervention. The one thing a child with dyslexia absolutely does not need is the “eclectic” approach to teaching reading. English is a rules-based language and

it does make perfect sense. When children with dyslexia are taught the structure of the language explicitly, systematically and in a multisensory way, they learn to read and spell. This type of approach is commonly referred to as the Orton-Gillingham

approach, which can manifest in prepackaged programs like the Wilson Reading System and the Barton Reading and Spelling program. But the program is only half the recipe: The teacher needs to be highly trained in order to be the most effective.

The takeaway here is that we know what works, so why not embrace it? -

Students with dyslexia need sensible accommodations. In addition to the intervention mentioned above, students with dyslexia need accommodations to access the curriculum. Remember that dyslexia is not an intellectual issue, so when

children with dyslexia cannot access the curricula via the traditional method of reading and writing, they need accommodations. The most beneficial accommodations are books on audio. These can be accessed through organizations like Bookshare and Learning Ally. It cannot be overstated how important it is to allow these students to learn via reading by ear. Students with dyslexia usually struggle with spelling and writing. They may tell

you a great story verbally and then write, “The cat sat.” So we can provide them with speech-to-text and now they can dictate their thoughts. You can visit the Headstrong Nation website for videos

about how to incorporate accommodations into the classroom. The takeaway here is that the purpose of education is to evaluate what they know and what they think, not how much they remember after struggling through a text that

is too hard for them. They have the brains—we need to give them the access. - Dyslexia is recognized by all school districts. It is not uncommon to hear “My school district does not recognize dyslexia” or “We don’t work with dyslexia at this school.” The truth of the matter is that every school in this country

recognizes dyslexia because it is written into the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), and it’s been there for over 35 years. You can read it here:Definition: Specific Learning Disability means a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think,

speak, read, write, spell, or do mathematical calculations, including conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia. - One teacher can make all the difference in the life of a child with dyslexia. It is common for a teacher to be reluctant to utter the word dyslexia. But if a teacher has done his or her research and has suspicions that dyslexia

might be the culprit of a child’s difficulty, the resources you give to the parent and the red flags you raise may be the difference between that child having a successful academic career and that child failing to meet his or her potential. You

can click here for a free resource about dyslexia and here: DyslexiaInTheClassroom.pdf

Ask the average person on the street what dyslexia is, and you will get a plethora of incorrect and absurd responses. So take a moment to read the following sentence:

The bottob line it thit it doet exitt, no bitter whit nibe teotle give it (i.e. ttecific leirning ditibility, etc). In fict, iccording to Tilly Thiywitz (2003) itt trevilence it ictuilly one in five children, which it twenty tercent.

How was that? Frustrating? Slow? What were those two sentences about? Don’t know? Why not? Did your difficulty understanding that sentence have anything to do with your intelligence? You now have the power to help a child with dyslexia who experiences

this frustration every time they read. Think on it.

Kelli is the co-founder of the Dyslexia Training Institute, which provides online training for those seeking information about and training for dyslexia. She is a certified Special Education Advocate and writes popular blogs about advocating for students with dyslexia. She received her doctorate in literacy with a specialization in reading and dyslexia from San Diego State University and the University of San Diego.