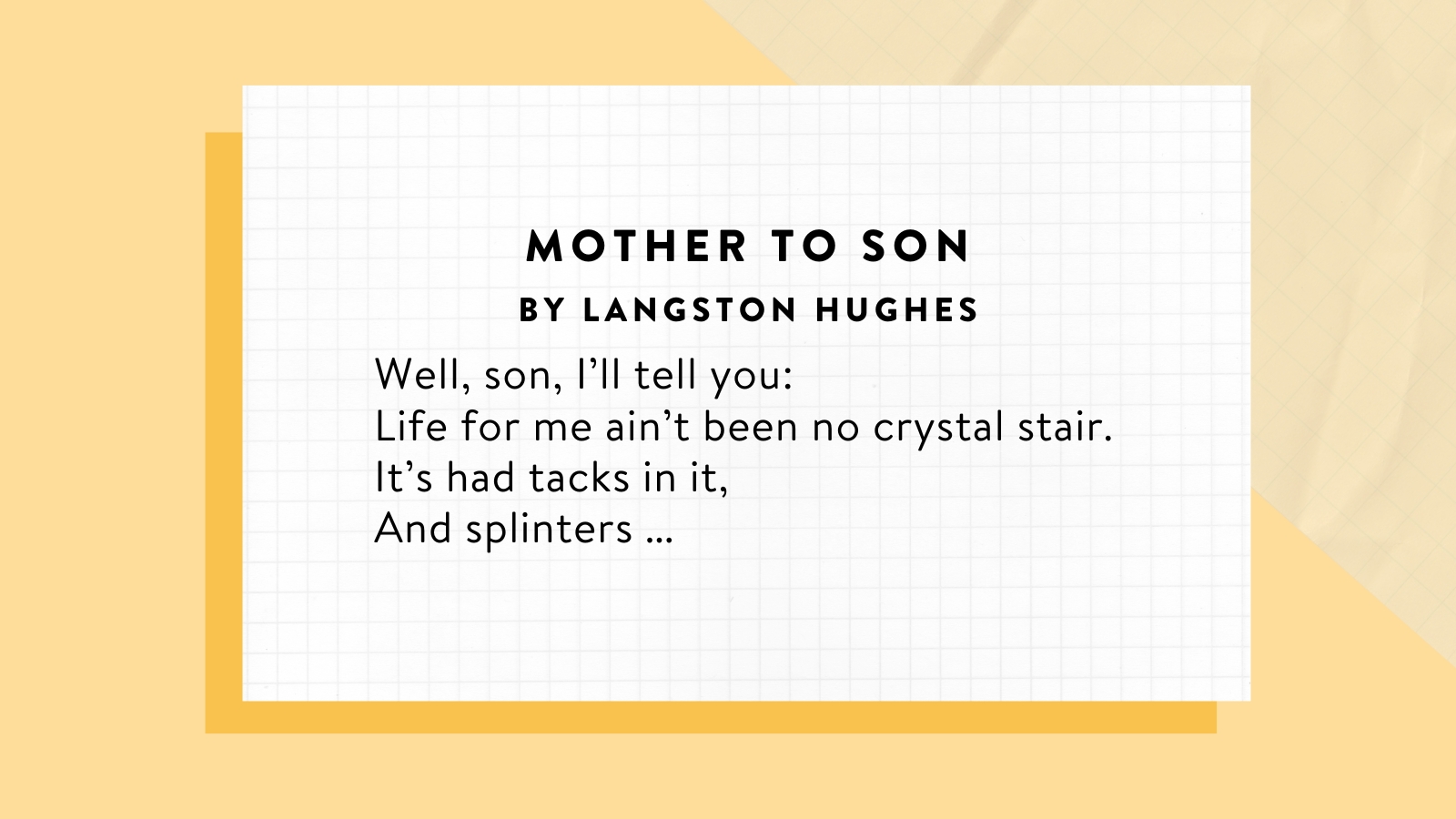

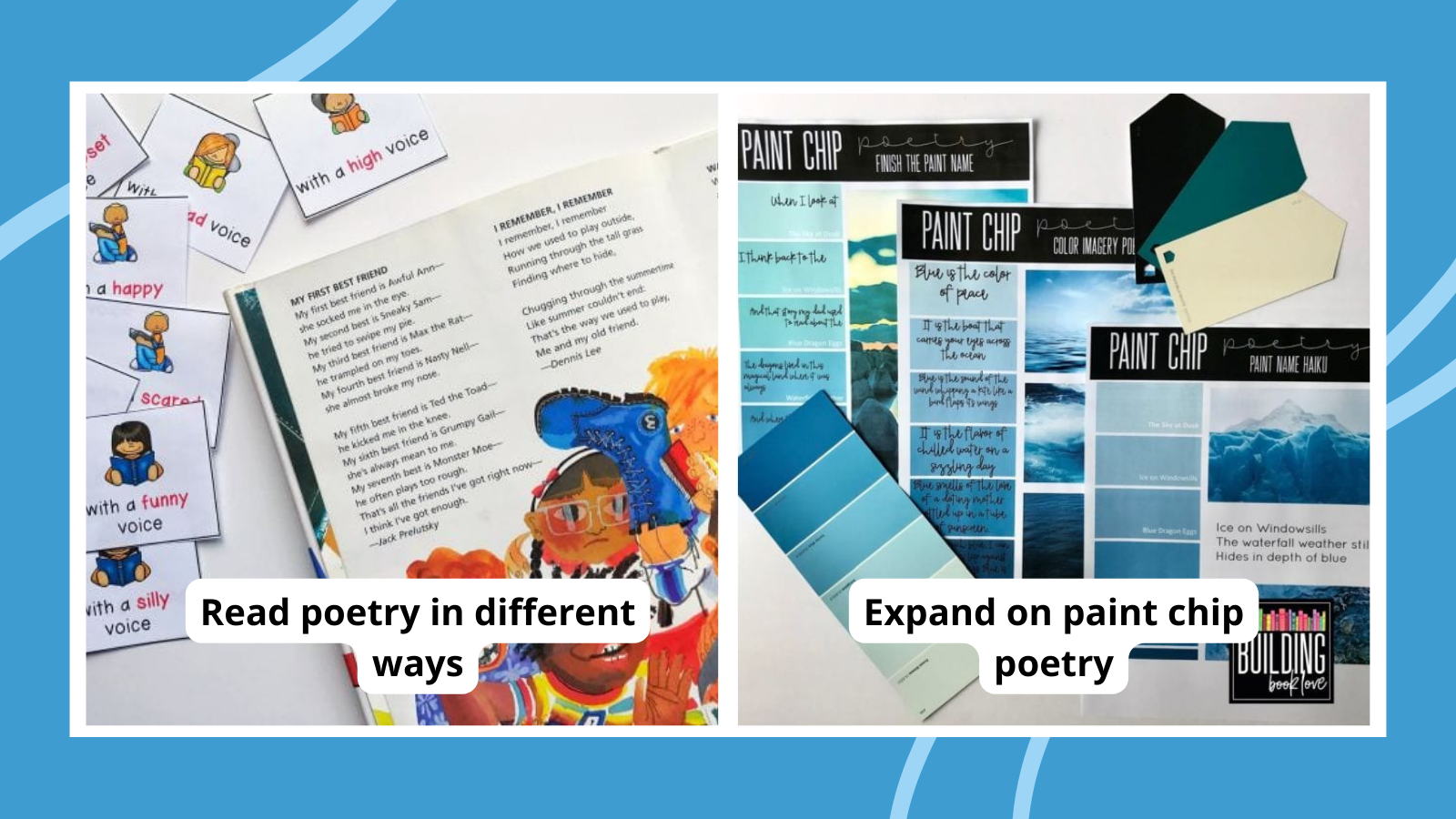

40 Inspiring Poetry Games and Activities for Kids and Teens

27+ Best Autism Resources for Educators

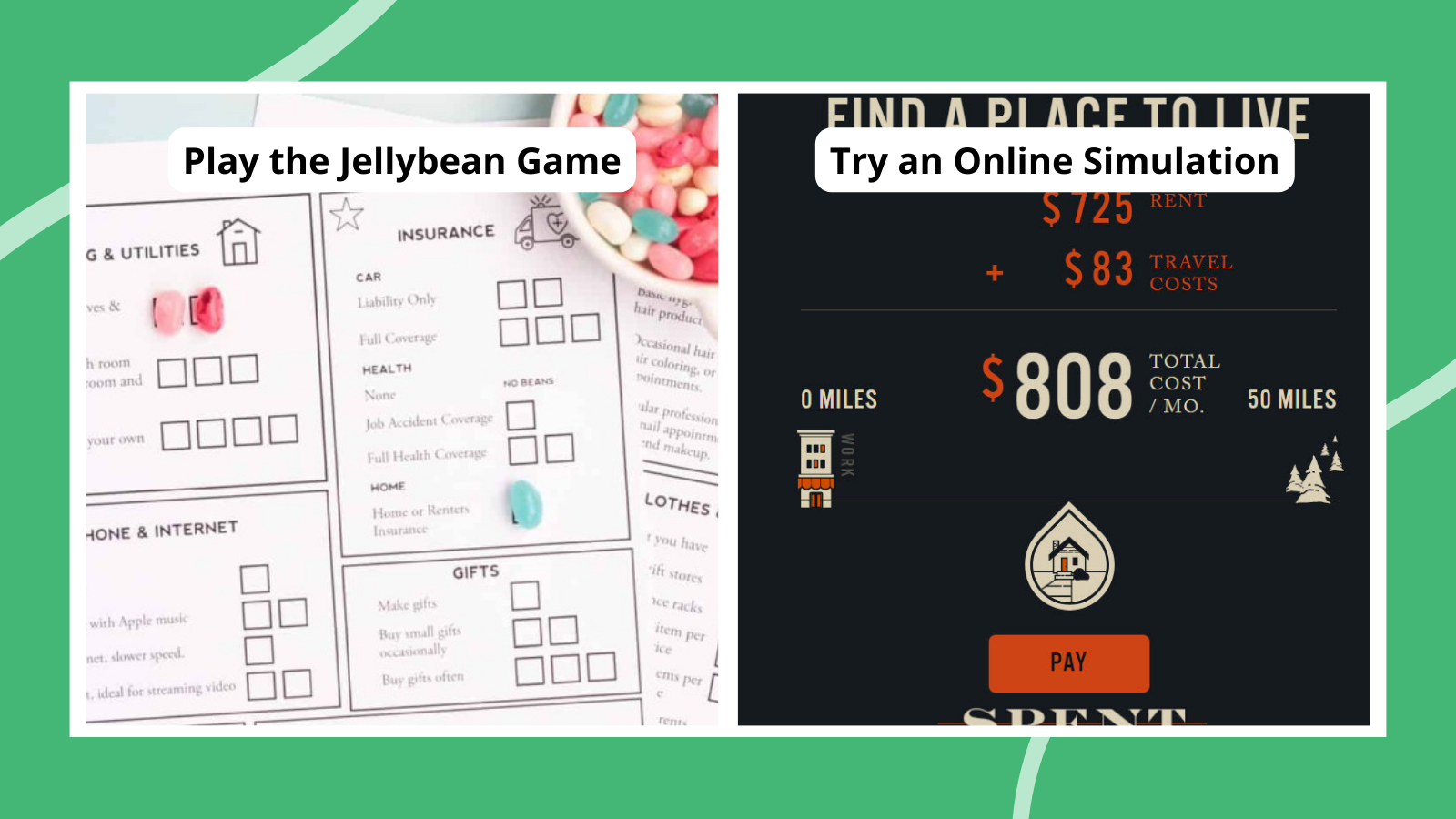

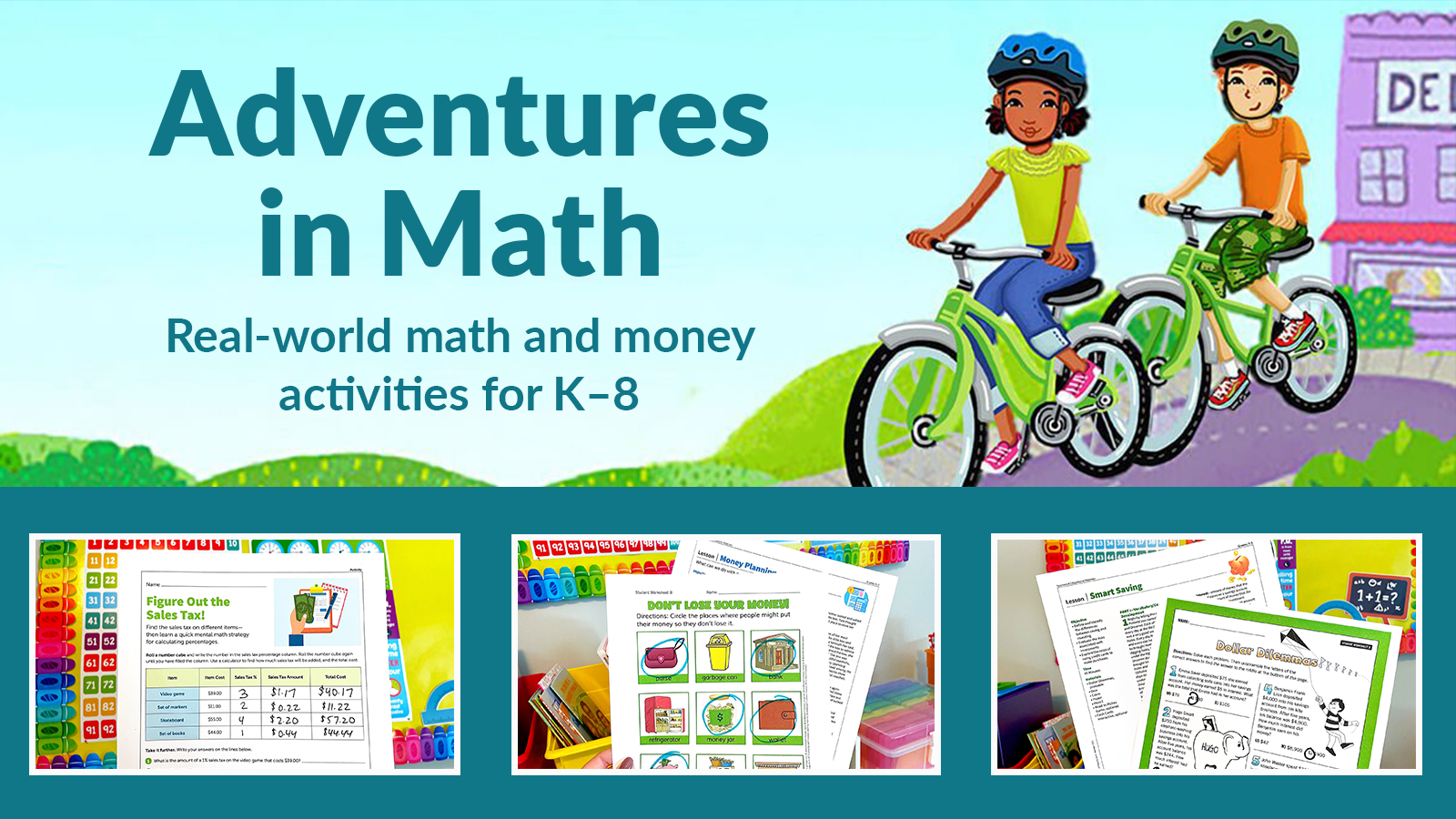

Financial Literacy for Kids: Lessons, Activities, and Teaching Tips

Top Stories

Get Our Free Spring Posters & Bring a Spot of Sunshine to Your Classroom

Hope, growth, and happiness.

Classroom Ideas

Browse by Topic

Discover classroom ideas, teaching strategies, and actionable tips for the subjects you teach every day.

Reading

Our top teacher-approved book lists, reading tips, and so much more!

Math

Find tips, resources, lesson plans, and games for K-12 that make math teachers’ lives easier.

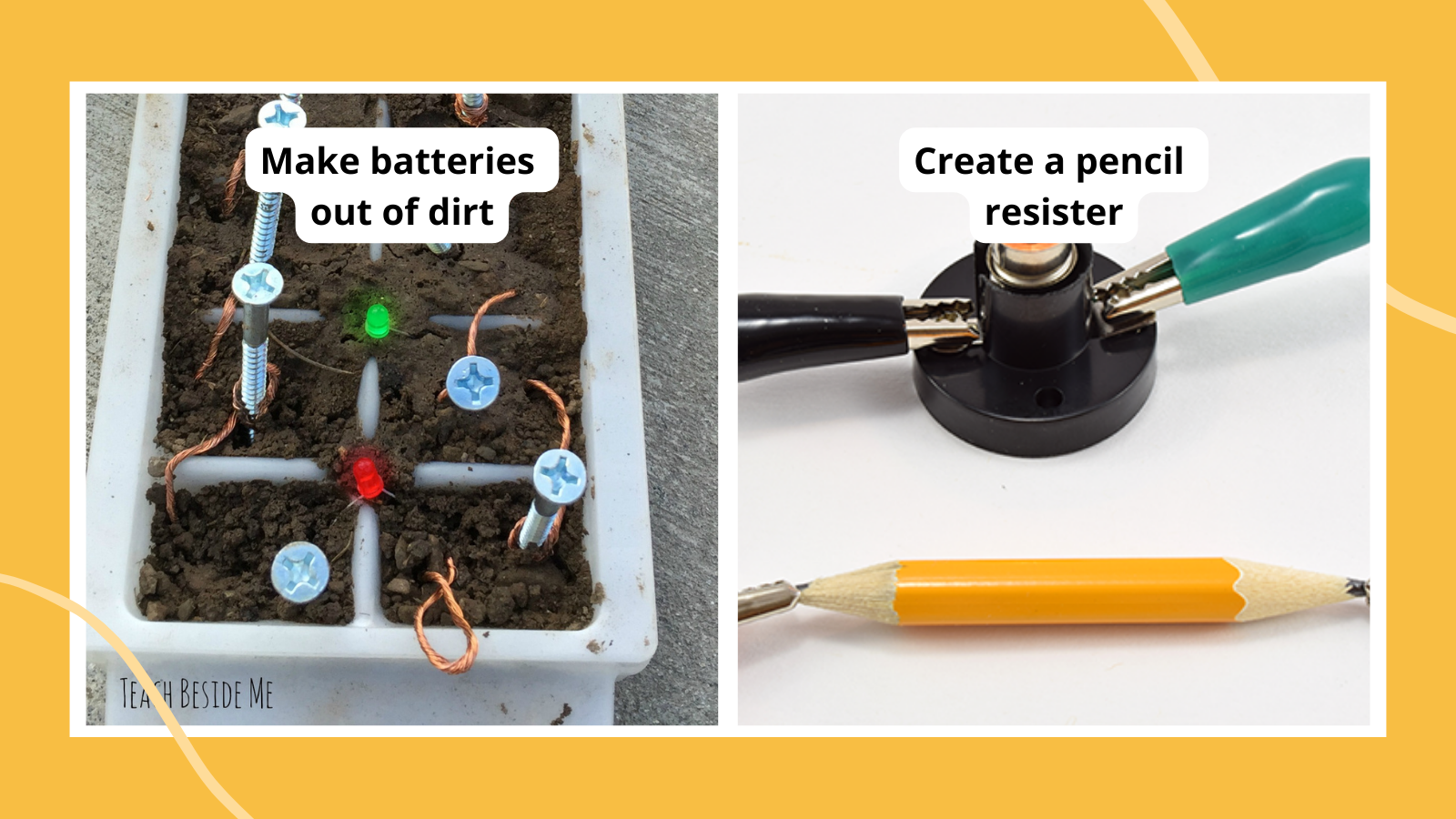

Science

Science experiments, lesson plans, science themed books, and more!

Arts

Find everything from creative ideas for using music and theater at school to craft projects you’ll love.

ESL

Tips for English as a Second Language and English Language Learner teachers.

Social Studies

Economics, history, geography, sociology, anthropology, psychology … we have you covered.