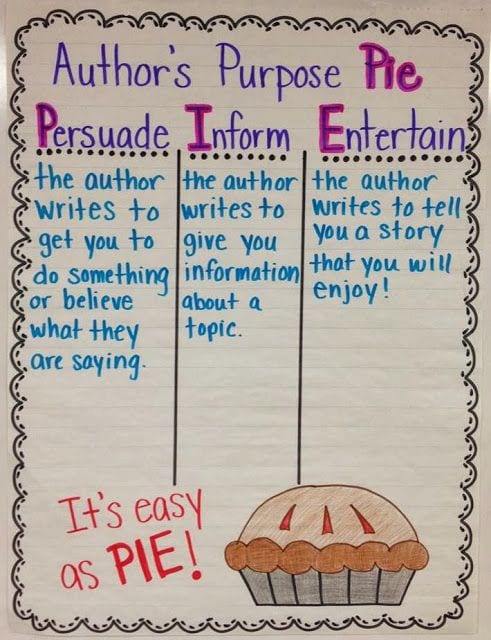

If you teach students about author’s purpose, you probably already know about the acronym PIE (persuade, inform, entertain) and the related cutesy anchor charts.

SOURCE: Teacherific Fun

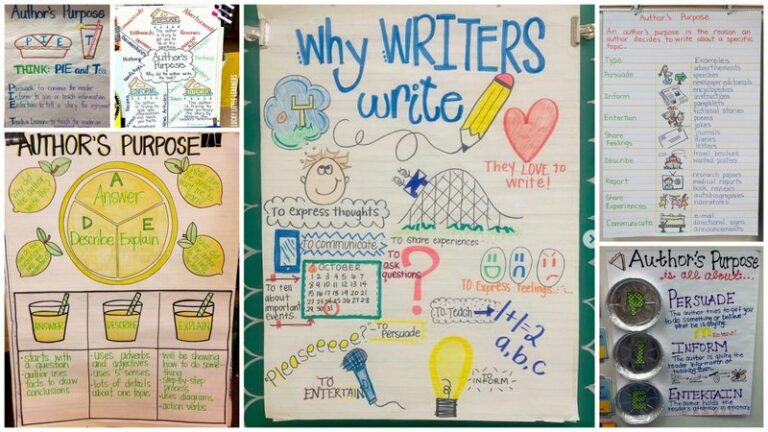

While those are good umbrella categories, the actual reasons that authors write nonfiction are often more nuanced. Textbook authors write to educate. Bloggers write because they’re passionate about a topic. Journalists write to disseminate information.

Today’s students are surrounded by information. The ability to figure out exactly why authors write—and not accept every opinion as fact—is a key skill. In particular, as students read, they’ll need to figure out the author’s purpose, identify bias, and draw their own conclusions.

As students get more advanced in their work with informational text, these five strategies will teach them how to figure out why authors really write.

1. Start with why.

“Why did the author write this piece?” is the core question asked to identify author’s purpose. To help students expand their understanding of “why,” post various types of nonfiction (an advertisement, opinion article, news article, etc.) around your classroom and have students quickly identify a purpose for each. Or keep a running author’s purpose board with a list of the various reasons why authors write.

2. Talk about structure.

Authors use different structures—sequence, problem and solution, compare and contrast—for different purposes. For example, one author may use sequence to explain an event, while another author uses compare and contrast to put that event into perspective.

3. Get to the heart.

Often when authors write, they’re trying to get readers to feel a certain way. Perhaps the author of an article about whale conservation wants readers to feel sad about the plight of whales. Or the author of a letter may want to make the recipient feel better about a situation. After students read a text, stop and ask: How do you feel? And how did the author get you to feel this way?

4. Connect to students’ own writing.

Writing and reading go hand in hand. Expand students’ awareness of why people write by having them write for different purposes. When students are charged to write about a topic that they think everyone should know about, to explain a procedure, or to share a personal memory, they’ll become more aware of how authors approach writing.

5. Observe how purpose changes within a text.

Author’s purpose is often studied through the text as a whole, but authors have different reasons for writing within texts as well. For example, an author may include a funny anecdote to draw in the reader. Then, they may launch into a list of facts that make the reader feel frustrated about the situation. And finally, they may conclude with an appeal. Take a short article and break it apart, identifying the different purposes so that students see how author’s purpose changes as they read.

Bonus: Three ways to teach kids how to identify bias

Right now, your students may take every nonfiction reading at face value, but as they develop as readers (and consumers of information), they need to learn how to evaluate bias.

1. Mind the gap.

When authors are writing to convince their readers of something, they’re choosing evidence that best makes their case. Have students read for an eye toward what information isn’t there. For example, if an author is writing in support of keeping horse-drawn buggies in New York City legal, they may include examples of the benefits (e.g., tourism) and leave out the drawbacks (e.g., horses holding up traffic).

2. Review the experts.

Have students pull out the names and titles of the people cited in an article. What can students learn from whom was included? And how credible is each expert?

3. Seek out stats.

Pull out statistics, images, facts, graphics, and other numbers to paint another picture of how the author is thinking. Based on the information, what does the author want readers to remember? What was included? What wasn’t included?

Every time kids read, they engage in conversation with the author, and knowing the author’s purpose makes that conversation that much richer.